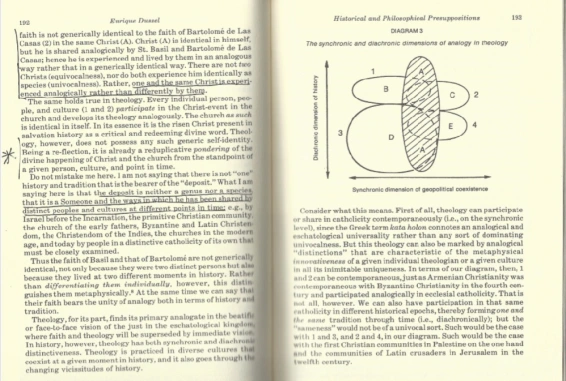

This is one of those “I have more reading to do, but . . . ” posts. Some context, first of all: as part of a chapter, on New World rhetoric(s), for the book project, I’ve been reading essays by the early 20th-century Peruvian socialist José Carlos Mariátegui and Latin American liberation theologians of the ’70s and ’80s. The former was an important influence on the latter, in that each believed that socioeconomic theory and theology, respectively, had to have as their starting points the actual conditions of–and solidarity with–the people being witnessed to (that verb being as appropriate a description for Mariátegui’s arguments for a distinctly Latin American style of socialism as it is for describing clergy and laypeople engaged in making the arguments for a theology of liberation). While my reading has so far confirmed all of this for me, the reason for this post is the diagram you see below and its strong evocation by analogy of Cuban theorist Severo Sarduy’s discussion of the Neo-Baroque.

from Enrique Dussel’s “Historical and Philosophical Presuppositions for Latin American Theology,” found here.

In this chart, Dussel seeks to illustrate his argument that, as represented by the shaded area of the chart, the Church throughout history has always held in common the divinity of Jesus as the Son of God and that humankind finds its salvation through belief in him. At the same time, however, “We can also have participation in that same catholicity in different historical epochs, thereby forming one and the same tradition through time (i.e., diachronically); but the “sameness” would not be of a univocal sort” due to the “analogical ‘distinctions’ that are characteristic of the metaphysical innovativeness of a given theologian or a given culture in all its inimitable uniqueness” (193; italics are Dussel’s). This recognition that the Church is located in particular spaces and times may seem quite obvious, but theologians of liberation use as their starting point the recognition that European theologies would too often presume that their teachings have always and everywhere been true, which had the effect of marginalizing non-Europeans and the non-powerful.

All those ellipsoid shapes in Dussel’s diagram are where Sarduy and his discussions of the Baroque come in. In his essay “Baroque Cosmology: Kepler,” Sarduy argues (and I’ll be quoting from an earlier post of mine),

“Though Copernicus’s heliocentric model of the cosmos (and Galileo’s confirmation of it) was indeed truer than Ptolemy’s description, it nevertheless retained the circle as its shape and thus, for Sarduy, implicitly continues to value a social politics in which power emanates from a single, clearly defined center.”

Kepler’s discovery that the planets orbit the Sun in ellipsoid orbits, by contrast, Sarduy says,

alter[s] the scientific foundation on which rested the entire knowledge of the age [and] create[s] a reference point in relation to which all symbolic activity, explicitly or not, is situated. Something is decentering itself, or rather, duplicating, dividing its center; now, the dominant figure is not the circle, with its single, radiating, luminous, paternal center, but the ellipse, which opposes this visible focal point with another, equally functional, equally real, albeit closed off, dead, nocturnal, the blind center, the other side of the Sun’s germinative yang, that which is absent. ( “Baroque Cosmology: Kepler” (trans. Christopher Winks), p. 293 in Baroque New Worlds.)

I have much to say in that earlier post about how the brute facts of the Americas’ landmasses, its indigenous flora, fauna, and peoples and, later, its mixed-race populations are the cause of the decentering that Sarduy describes. For now, I’ll just add here that those theologians of liberation whose work I’ve read likewise note that, as Juan Carlos Scannone puts it, “it would be a completely new reworking and formulation of theological activity as a whole from a completely new standpoint: i.e., the kairos of salvation history now being lived on our continent” (215). Dussel’s discussion of the various manifestations of the Church as having, in effect, dual centers of attention is a direct reflection of that new standpoint as well.

As I said at the beginning of this post, I have more reading to do; moreover, what you see above is no more than a sketching-out of these links. But it’s a good feeling to see some initial confirmation of some claims I’m making even when I’m not actively looking for something to confirm my biases.

José Carlos Mariátegui: An Anthology, ed. and trans. by Harry E. Vanden and Marc Becker (Monthly Review Press, 2011).

José Carlos Mariátegui: An Anthology, ed. and trans. by Harry E. Vanden and Marc Becker (Monthly Review Press, 2011).